We previously discussed shamanic initiations which involved visions of descent to the underworld. There the candidate experienced ordeals of death and dismemberment prior to rebirth and attainment of shamanic powers. This age-old drama of spiritual catharsis and transformation has uncanny parallels in the Sumerian myth of Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld, the oldest recorded myth of a journey to the netherworld, composed sometime between 1900 and 3500 BCE.

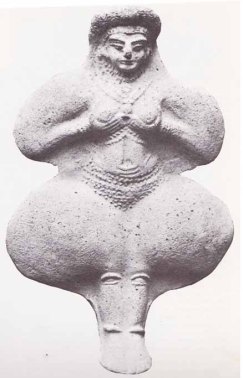

The goddess Inanna derives her name from the Sumerian words nin-anna meaning “queen of heaven”, and she was aptly associated with Venus, the brightest planet in the heavens. Embodying the contrasts of nature, Inanna was a goddess of love as well as war, the alluring goddess of fertility and sexual passion who also delighted in stirring up rage on the battlefield. In her appearance as the evening star on the western horizon, Venus/Inanna assumed her role as gentle love goddess. However when she appeared as the morning star heralding sunrise, she became the fierce goddess of war. One of the most popular and beloved goddesses of ancient Mesopotamia, people could identify with Inanna’s all too human passions and swings of behavior—her tenderness, promiscuity, jealousy, anger, and hubris, described in many stories.

In the myth of Inanna’s Decent to the Underworld, the goddess decides to journey to the land of the dead, ruled by her sister Erishkegal, to participate in the funeral rites of Erishkegal’s husband, the Bull of Heaven. This is a bold act, perhaps prompted by Inanna’s ambition to extend her rule to the world below. Inanna knows full well that none who descend to the netherworld ever return. Accordingly she instructs her trusted messenger Ninshubur before her departure that he should go and “weep” before the gods, so they will come to her rescue should she not return after three days.

After a long journey Inanna arrives at the gate of her sister’s palace in the land of the dead. She arrogantly bangs on the door, even threatening to break the bolts if she is not let in. Angered by her brashness, her sister Erishkegal instructs her doorman to open the gates for her. She is told she can enter only on the condition she surrenders one of her “divine powers” at each of the seven gates: her turban, her lapis measuring rod, jewelry and clothes. By the last and seventh gate Inanna is stripped bare. Naked and bowed low she enters Erishkegal’s palace where she attempts to sit on her sister’s throne. Enraged by her arrogant behavior, Erishkegal calls for Inanna’s death. She is judged by seven judges, the Anunnaki gods, then struck and killed by Erishkegal. Inanna’s corpse, like a piece of rotting meat, is hung on a hook on the wall.

As previously instructed, Inanna’s messenger approaches various gods for help, including her father Nanna the moon-god. Nanna ignores his pleas, stating that those arrogant enough to crave the divine powers of the underworld must remain there. Finally, Enki the god of wisdom and magic takes pity on Inanna’s plight and agrees to come to her aid. He creates two figures named Galatur and Kurgarra from the dirt under the fingernails of the gods. They are told to go to the palace of Erishkegal and “enter the door like flies”. When they arrive there they find Erishkegal moaning and crying like a woman ready to give birth, and appease her by expressing concern for her suffering. In gratitude, she asks them what they want in return. Without hesitating they ask for Inanna’s corpse, which they then sprinkle with the magical “water of life” and “life-giving plant”, given to them by Enki. Inanna is revived, and flees from the underworld back to the world of the living. The demons, however, chase after her demanding a replacement.

Inanna returns home to her palace to find her husband Dumuzi sitting on her throne. In fact, during her absence he didn’t even bother to mourn her loss. Enraged at his lack of concern, she gives the ungrateful man to the demons to take. Dumuzi’s sister Geshtinanna steps forward and volunteers to take his place. Brother and sister agree to alternate, each living in the underworld for half a year, and on the surface world the other half.

Historian Goeffry Ashe stresses the shamanic motifs of the myth. He points out that the story is similar to the trance descents to the underworld performed by Altaic shamans or shamanesses: “Inanna dons a septenary outfit with septenary magical gear. On the way she passses through the ordeal of the seven gates, just as the shaman passes through the seven pudak, or obstacles.” The seven pudak Ashe refers to are the seven levels of the underworld, similar to the seven gates entered by Inanna. The basic structure of the older shamanic myth—the underworld descent—followed by the ordeal of death, then rebirth and return of the shaman to the world of the living was preserved by the Mesopotamians, yet altered to accommodate their agricultural mythos. The shaman’s role is now played by fertility deities—Inanna, as well as her husband Dumuzi—who becomes the sacrificial victim demanded by the powers of the underworld.

Dumuzi as the husband and lover of Inanna was called the “shepherd”, who helped the sheep multiply and the grain grow. He personified the yearly cycle of natural growth. It was believed his mating with Inanna in the spring caused the earth to blossom. During the heat of the summer when the crops withered and died it was thought he had descended to live in the underworld. During the period of Dumuzi’s confinement there, he was mourned by funeral rites as the sacrificial Wild Bull. This practice was so widespread that the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel witnessed it at the temple in Jerusalem, scornfully commenting: “…behold, women were sitting there weeping for Tammuz”. Tammuz/Dumuzi was reborn and returned to the world every autumn, along with the life giving rains, bringing fertility to the crops. His joyful reunion with Inanna was widely celebrated in the ancient Middle East.

We can see here the reiteration of the myth of the goddess and the bull, mentioned in previous posts, which was widespread throughout the Neolithic and Bronze Age, in which the bull-god, lover and husband of the goddess, is sacrificed to sustain the world. Savior gods of the ancient Mediterranean world such as Dionysus, Osiris and Attis all have associations with the sacrificial bull. They were “dying gods” who were sacrificed and resurrected, symbolizing the mystery of nature’s eternal cycle of death and regeneration. According to Joseph Campbell, both Inanna and her sister Erishkegal can be understood as two sides of one goddess—representing her powers of life as well as death. As Inanna’s body hangs lifeless on a hook, Erishkegal groans in childbirth—from death springs new life. Paradoxically, as well as being the realm of death, the underworld is also the source of regeneration and life.

There is an astronomical dimension to the myth as well that was clearly understood by Mesopotamian astronomer-priests. The planet Venus, a manifestation of Inanna, always travels in close proximity to the sun as seen from the earth. It leads or follows the sun in the sky—never more than forty-eight degrees apart from it. Venus sets after the sun during certain phases of its orbit as the Evening Star, and rises before the Sun as the Morning Star during other phases. When Venus closely approaches or “transits” the Sun it disappears into its light—vanishing from sight. This can last from a few days to as long as three weeks. This period of Venus’ disappearance was understood as Inanna’s confinement and death in the underworld. Eventually Venus would be seen rising on the opposite horizon to which it was last sighted, which was interpreted as Inanna’s rebirth and return to the land of the living.

Inanna’s descent can be viewed as an allegory of individual spiritual awakening that is as relevant today as in ancient times. Writing about the myth, assyriologist Simo Parpola states: “…the goddess plays the role of a fallen but resurrected soul, thus opening the possibility of spiritual rebirth and salvation to anyone ready to tread her path.” Without descending to the depths—becoming aware of one’s “shadow” or unconscious self—ascent to the light cannot genuinely occur. To quote Carl Jung: “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious”. Inanna and Erishkegal—the light and dark sides of the goddess—are inseparable aspects of the alchemical process of transformation of the soul.

Great post! Thank you for writing it!

LikeLike

Hadn’t really thought of Inanna’s journey to the underworld, but it definitely is. Thank you.

LikeLike

Yes, the premise of the book is that shamanism is the substratum of most later mythologies which were grafted onto the earlier beliefs and practices. BTW sorry I missed your lecture last night Chrissie…I wanted to go but circumstances prevented.

LikeLike